Claimed by God: On Firstborns, Levites, and Layered Belonging

Jewish life often seems to pull us in two directions at once…

✍️ A Note from Miriam

While I’m traveling in Argentina this week, I’ve asked someone whose voice I deeply trust to share Torah with you in my place. I’m honored to introduce this week’s essay by my teacher, mentor, and dear friend Peninah Engel. Peninah’s depth of Jewish knowledge is vast, her bookshelf seemingly infinite, and her insights have shaped my thinking in more ways than I can count. I’m so grateful to her for stepping in — and so excited for you to learn from her too.

I’ll be back next week—with reflections from the southern hemisphere.

For now, enjoy and Shabbat Shalom.

—Miriam

PS For a printer friendly version’s of this week’s newsletter, click here.

🏕️ Claimed by God: On Firstborns, Levites, and Layered Belonging

by Peninah Engel

Jewish life often seems to pull us in two directions at once, presenting us with a role in our families as well as responsibilities towards our communities as a whole. The Israelites find in the wilderness that God has a specific vision for their community that must be fulfilled as they journey towards the Promised Land, and they must learn to integrate their existing familial allegiances into the Divine plan in order to proceed. Sefer Bamidbar, the “book of the desert”, which we are starting this week, will contain stories of group cohesion and tension, showing the ways that individual Israelites navigate their shared destiny, while the nation as a whole struggles through 38 years in the wilderness.

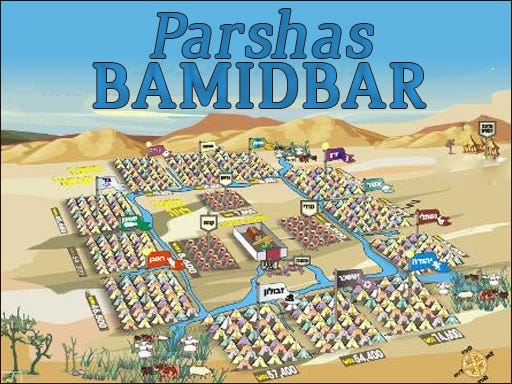

Parshat Bamidbar picks up with instructions from God to Moshe near Mt. Sinai. The business of the day is counting the Children of Israel, naming their leaders, and placing the twelve tribes into camping groups. This count is depicted as a military muster, counting men over the age of 20. A ‘nasi’ or ‘elevated person’ (often translated ‘chieftain’ or ‘prince’) is named for each of the twelve non-Levite tribes, and together with Moshe and Aharon, they count 603,550 Israelite men. Then each camping group of three tribes is assigned to one of the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west of the Mishkan) to complete the spatial layout of the Israelite camp.

Then the last remaining tribe, Levi, who were not included in the general count, are considered. This tribe is broken up into three families of Gershon, Kehat, and Merari. Each family is counted and assigned a camping location and set of responsibilities in the Mishkan. The Cohanim, the Priestly family consisting of Aharon and his sons, is also singled out. God assigns them responsibility for protecting Levites from violating the sanctity of the Mishkan, and Elazar son of Aharon is called ‘nesi nesiei Levi’ – ‘the one elevated from among the elevated people of Levi.’ All 22,000 Levites are counted – Kehat and Merari in detail this week, Gershon next week.

Trading Places, Elevating Levites

So far, the Torah has determined each Israelite’s role in the collective based on their family, with group identity determining how close each member of the community should be to Divine service. Regular Israelites are furthest – spatially and metaphorically – from God’s presence, then Levites, then Priests. This type of organization is not given an explanation beyond the refrains familiar from Leviticus – “they will be Mine,” and “they will be sacred (kadosh).” Perhaps in a society where land and livelihood were based on the kinship structure of a ‘beit av’ or paternal dynasty, it was obvious to the Israelites that an individual’s role serving God should be dynastic too. However, at the end of this parsha, God offers a new rationale for the sanctification of the Levites.

“As for me, I hereby take the Levites from the midst of the Children of Israel, in place of every firstborn, breacher of womb from the Children of Israel. They are to be mine, the Levites. For mine is every firstborn. At the time that I struck down every firstborn in the land of Egypt, I hallowed to me every firstborn in Israel, from man to beast. Mine are they to be; I am YHWH!”

— Numbers 3:12-13

Then the Levites are actually exchanged with the firstborns. This exchange is done so literally that when the count finds 273 more firstborns than Levites, those “extra” men are redeemed for a sum of money paid to the Priests.

Why do the Levites need this additional route to elevation? Isn’t their hereditary status as descendants of Levi enough to assure them a sacred position, and make them belong to God?

There is a more practical question here too. Firstborn sons in the Torah have special status in their families beyond their belonging to God – in the Torah’s vision of patriarchy, they inherit a double portion from their fathers, they are presumed to take over leadership of their families in the next generation, and they are described evocatively (Deut. 21:17) as “reishit ono,” the father’s first effort.

There is an obvious metaphorical meaning to the most socially favored people from each family “belonging” to God – that worship of God is the highest calling a privileged person could pursue. How could that meaning be transferable to the Levites, a group of non-firstborn people, who don’t all experience the special privilege a firstborn would?

A New Period of History

The Rabbis of the Mishna explain that what is being transferred here is the responsibility to perform the Priestly service that previously in Israelite tradition was the role of firstborn sons.

“When the Mishkan had not yet been established, private altars were permitted and the sacrificial service was done by the firstborns. Once the Mishkan was established, private altars were prohibited and the sacrificial service was performed by the priests.”

-Zevachim 14:4

This interpretation defines the swap narrowly – only the sacrificial privileges are being transferred from firstborns to Levites, and the only Levites who can actually follow through on the privileges are the Priests. Entering the historical period of centralized Mishkan service means that Israelites must limit sacrifices to one family group, to correspond to the one permitted location for worship. Also, some classical Rabbinic sources find fault with the firstborns that lost them their sacrificial privileges. They link this to the sin of the Golden Calf, when Israelites, including firstborns, worshipped the graven image while the Levites followed Moshe instead. This would be a tragedy for each Israelite family, which would in essence be losing its former privileges to access God.

However, it would be confusing for this to be the moment the firstborns lose their sacrificial privileges, as the Torah has never before mentioned firstborns performing sacrifices. Also, the Priests have already been extensively empowered to offer sacrifices before this swap. Commandments to offer sacrifices throughout Leviticus already refer to Aharon and his sons as the ones who will be performing the sacrificial service, and they’ve already been consecrated to this task with extensive ritual. It seems late to be transferring the sacrificial role from the firstborns to Priests at this point. Although there is a powerful lesson in this thinking of divine justice, it does not seem to represent the simple meaning of the ritual in our Parsha.

If Priests and not firstborns were already responsible for sacrifices, what other significance could this man-for-man trade have?

Claimed as Kin by the Divine

The firstborn son was a central metaphor during the Exodus, when God described the Divine affection for Israel to Moshe in this language, and provided the rationale for the final plague as a measure-for-measure punishment.

“Then you are to say to Pharaoh: Thus says YHWH: My son, my firstborn, is Israel! I said to you: Send free my son, that he may serve me, but you have refused to send him free, [so] here, I will kill your son, your firstborn!”

-Exodus 4:22-23

And in the instructions for how the Exodus is to be commemorated, when a future son asks his father about firstborn animals being offered as sacrifices, the father is meant to give an answer that includes an explanation of this same measure-for-measure scheme.

“It shall be when your son asks you in the future, saying: What does this mean? You are to say to him: By strength of hand YHWH brought us out of Egypt, out of a house of serfs. And when Pharaoh hardened against sending us free, YHWH killed every firstborn throughout the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of man to the firstborn of beast. Therefore I myself sacrifice to YHWH every breacher of a womb, the males, and every firstborn of my sons I redeem.”

-Exodus 13:14-15

God claims all the Israelites as “his firstborn son” explaining why Pharaoh’s subjugation of the people is intolerable using the metaphor of a human father’s love for his oldest son. God here does not object to the institution of forced labor, Pharaoh’s cruel and dehumanizing decrees, or declare any pre-ordained historical mission for the people, but simply compares Godself to a father who wants what is best for his favorite son.

The metaphor of family, even if it is not literally true, can bring extra power to collective identity. In ‘The Two Houses of Israel: State Formation and the Origins of Pan-Israelite Identity’ Omer Sergi uses archaeological inscriptions as well as texts to demonstrate how ancient Near Eastern societies, including Mari, Moab and Assyria, as well as the Israelite kingdoms based in Samaria and Jerusalem, understood themselves as one extended family. He writes:

“In essence, kinship relations were used to stretch time and space and to enable the conception of common identity with unknown others…Rather than bringing about the dissolution of kinship ties, the state contained them, incorporating kin-based communities within a more centralized, sometimes hierarchical structure.” (pp. 42-43)

In these tribes and kingdoms, a ruler’s whole capital city or region may be referred to as his ‘house’ and all the members of the group may be thought of as his “children” or “brothers.” God’s kinship-based rationale for performing the Exodus sanctifies this metaphor and extends it one step further. It is not just the political leader acting as a “father” to the people, but actually their God who steps into this role.

The powerful image of God as Israel’s father is developed further as the Torah describes for us the tent that God will use as a Mishkan, or dwelling, just as each family in the desert dwells in their own tent. In God’s home, the equivalent to the firstborn are the Levites who God has chosen, and the equivalent to the firstborn’s special privileges and responsibilities toward the family are the Levites’ roles in caring for the Mishkan and facilitating its spiritual use. The Torah concretizes this transfer through the ritual described in our parsha where the Levites are each exchanged for a firstborn. All Israelites are considered children to God, but Levites are here made especially precious children. The special status of firstborn sons as leaders is extended in God’s “family” to the whole tribe of Levi.

An Incomplete Takeover

Yet it is clear that despite this ritual transfer of status, firstborns remain firstborns and retain some of their special Divine belonging. The commandment to redeem firstborn sons will be repeated in a few weeks in Numbers 18:15. If the Levites have fully taken over the special status of the firstborns, why would the mitzvah to redeem firstborns persist?

This is where the literal aspect of trading firstborn for Levite breaks down. A firstborn is special in relation to their own family, qualitatively different from any other family’s firstborn, while a Levite’s role can be filled by any other member of their group. As much as this status-trading ritual may supplant the family-based power structure with a centralized one in relation to the Mishkan, the Israelites’ roles in their families simply cannot be traded away. We are special to our families in a way that is unique to each individual. In a society where firstborn sons are afforded special privileges within their homes, the Torah does not ask families to reject this norm. In fact, it preserves the special role of firstborns in other areas, even while using them as living metaphors to bring the Levites into prominence in the national family.

Members of Two Families

With our parsha’s ritual switching of firstborns for Levites, the Torah reinforces the idea that all Israelites belong to two different, overlapping families. Each Israelite has their own family of origin, where their role is dependent on their gender, their age, their place in the birth order, and their own family’s circumstances. But also, each person is part of a national “family” that includes not just human members but also the Divine, where the Mishkan is “home”, and the “children” are led by the “firstborn” Levites in the service of their Divine Father.

Both these “families” are important in the mitzvot that the Israelites must follow. Their home families inform how they will honor their parents, redeem their family’s landholdings, teach their children, and maintain sexual sanctity. But their larger, metaphorical “family” that includes all Israelites will guide their performance of mitzvot like giving Priestly gifts, loving the stranger, administering justice, and maintaining the purity of the Mishkan.

For Israelites in the desert, seeing their family’s firstborn step up to be “swapped” for a Levite would have given them the feeling of belonging to this new, national family. The 22,000 families who participated in a man-for-man swap and the 273 who redeemed their firstborns for silver now had a concrete investment in the family structure designed around the Mishkan, without giving up the special status that each individual had in their own family at home. And knowing that God thinks of all Israelites as one collective “firstborn son” would have spread the feeling of being uniquely treasured across the entire people.

Living in two layers of family

Without a Mishkan or Temple to concretize God’s chosen power-sharing system, how can we make use of these two levels of family to ensure connection with our family and communities?

In our modern practice of Judaism, many community institutions assume the roles that Levites or Priests are assigned in the Torah. A community-chosen chazzan might lead prayers at a synagogue, while a family member leads the singing at home. On holidays a Kohen offers the Priestly Blessing in the synagogue, and at home a parent blesses children with the same text every Friday night. A Rabbi or Jewish educator may be responsible for teaching a child to read the Torah, but it is often a sibling, grandparent, or role model at home who teaches them to live it when no one is watching. These dual “families” make the Jewish people stronger – when one community or one family fails, it is the other’s responsibility to step in.

Each type of structure has an advantage over the other – communal “families” are built to trade out one leader for another when circumstances change, while we may find that each family member at home is irreplaceable. Perhaps we can use the image of “trading” one family for another to think through the ways we can merge these aspects of our Jewish lives, by appreciating the things that are unique about our community leaders, or the moments in our family dynamics where we find ourselves stepping into a new role. This exchange in the wilderness isn’t about replacing one family with another—it’s about learning from both. We grow by letting our communal life inform how we show up at home, and by letting the differentiation of home shape how we serve the wider world.

Questions for Thought:

Can you become a leader in your community? How does your community choose its leaders? What communal tasks are being done on your behalf that you might be uniquely good at too, and can you get yourself chosen to help share this communal responsibility?

How does your family choose who will perform mitzvot at home? Is it always the same person? The next time you’re hanging a mezuzah, choosing a charity to support, or leading a ritual, how would it feel to choose a different family member to represent your household in this mitzvah?

The trade of firstborns for Levites and the metaphor of Israel as God’s firstborn both relate only to male members of a family or nation. In our own world, do these comparisons hold up as well as gender-neutral categories, or is there something distinctively male about these metaphors?

Rather than reading the exchange of Levites for firstborns as a transfer where each family loses access to the Divine Presence, we can see it as a moment where God recognizes the inherent importance of individual Israelite families in creating a nation. We benefit from belonging to multiple layers of community, where we can both blend in and stand out. Like the firstborns in the wilderness, we can enhance our communities’ institutions while continuing to perform the mitzvot in the spaces where we are irreplaceable.

May we carry that layered sense of belonging with us into Shabbat—honoring where we come from, and where we are called to serve.

Shabbat Shalom,

Peninah

❤️ If you liked this post, please hit that lil heart at the bottom of the page. It really helps!